Why all these labels?

It was a common occurrence while working in the NHS to receive a referral letter from a Paediatrician describing a child with “a little bit of ADHD, a moderate degree of ASD and a lot of dyspraxia” – sometimes in variable quantities! How must the parents feel, I would wonder, knowing their child has all these things ‘wrong’?

It does however fit with my understanding of the spectrum of abilities with strengths and weaknesses giving a pattern that points to more than one diagnosis.

This thought gained clarity while thinking how to describe dyspraxia to a group of mature students on an access to healthcare course. I had only previously provided training to parents and teachers who already knew how these children present. I had a ‘script’ prepared from these sessions but as I faced the group of expectant faces, I suddenly thought, “How do I introduce the concept of these mild motor difficulties to a group of people who haven’t experienced this first hand”?

I began by drawing a line which I referred to as ‘co-ordination’ and described how some people are well co-ordinated and others struggle. I then draw a line called ‘balance’ and challenged the class to stand on one leg for as long as they could. As expected, a bell curve developed with some balancing for only a short time, the majority balancing for between 10 – 20 seconds and a few being able to maintain their balance for longer. I then asked the group to rate their organisational abilities on a scale of 1 to 10 (on the promise of not divulging to their managers!). Again, a few acknowledged that they considered their organisation was a weakness, most scored themselves between 6-8 and just a couple gave themselves full marks. I proceeded to draw lines which I labelled ‘attention’, ‘activity level’, ‘sensory responses’, ‘social skills’ and ‘learning ability’ which was further subdivided into general and specific.

I then proceeded to make marks on the chart to show the profile of a child with dyspraxia. This affects co-ordination, balance, organisation, usually sensory reactions and subsequently social skills. Attention can also be poor. Learning ability can be anywhere in the range, but the definition of dyspraxia (formally diagnosed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual as Developmental Co-ordination Disorder) is that motor difficulties must be below that of general developmental level. This gives a profile as below.

In ASD, social skills are highly affected, and sensory reactions tend to be more extreme than seen in dyspraxia. Attention to task can be low if it is an adult initiated task and very high to the exclusion of all else if the child is engaged in a special interest. Organisation can be poor but can also be extremely high and rigid (e.g. belongings in room stored in height or alphabetical order). As in all things, the question is, does this cause a problem? A drive to categorise is highly desirable in a career in a library; becoming physically aggressive if Mum’s dusting has moved an item by 2mm is not.

With ADHD, the clue is in the title! These children have poor attention and a high activity level. Again, however, other areas of difficulty can co-exist. The ‘fast’ running of the nervous system can result in sensory sensitivities and sensory seeking behaviours. This in turn can affect motor skills either due to moving too fast or not being still long enough to master fine motor skills. The lack of time taken to think, leading to impulsivity, will also affect organisation.

Learning ability is known to fall onto the bell curve with a small number at either end indicating severe learning difficulties or genius, and the vast majority in the low to high average range. Similarly therefore, specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia and dyscalculia can also range from severe to mild. Again, some children with these conditions may also have difficulties with motor skills, sensory reactions, organisation etc.

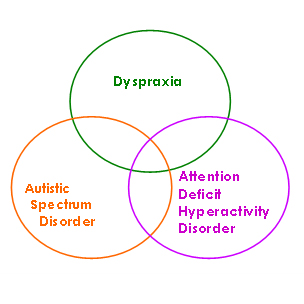

When children have difficulties in a number of these continuums of ability, they can present with a Venn diagram of conditions that have overlapping features.

Hence a ‘little of this, a lot of that’. For some time now this co-morbidity (conditions that commonly exist together) has been acknowledged. In the Scandinavian countries this cluster is known as Disorders of Attention, Motor and Perception; unsurprisingly however, the acronym of DAMP has not taken on in this country!

As a therapist, this continuums model helps me to identify areas in which a child needs intervention. The goal is then to make progress towards the functioning range. Often the question arises, “Does this child have Dyspraxia?”. With some children, this is clear to see one way or the other. Others fall into the middle ground of there being some signs but it is not fully conclusive. Seeing features of these conditions as being on continuums of normal development will inevitably place some children in the grey area. And what of the effects of intervention? I have worked with children with marked dyspraxia whose abilities progressed from severe to mild. If children are already only mildly affected, does that mean that with intervention they will no longer have ‘it’?

To label or not to label….?

That is a question I have often been asked. And like many black or white questions, the answer is “it depends”. It depends on what is to be achieved. Will diagnosis enable those supporting a child, be it family or teachers, know how best to help? Often, the answer to this is yes, but I have seen many children whose parents are not seeking formal diagnosis but are keen for intervention and do all they can to meet their child’s needs. Will it help the child to know? Again, this depends on the child, and the response can be marked in both and negative and positive ways. Depending on how this is done and the temperament of the child, some children will rest back on the diagnosis and say “I can’t do that because I’ve got…” To be fair to the child, they’ve probably had years of giving it their all and it never being good enough, that they are ready to sit back and blame the condition. However, this needs challenging if they are to go on and live a productive and fulfilling life. Sadly, their reality is “Because you’ve got… it’s going to be tougher for you… but we will help”. On the flip side, I have known many children who are massively relieved to learn that their brain works in a different way to other people. These children can often take on board simple neuroscience and learn strategies for improving their sensory processing. I recall a 13 year old who had been listening to feedback of his OT assessment observe his younger brother enter the room and push up on a chair – “Ah, seeking proprioception”, he wryly commented!

For parents, rather than focusing on “we knew he’d got this, now he’s also got that”, it can be helpful to see their child’s abilities as being on a continuum of development rather than as a disorder. This can facilitate their understanding of the different ways to assist their child to progress along the continuums to a satisfactory range of function.

On a personal note

As a parent of a child with dual diagnosis of ASD and dyspraxia, plus the legacy of early poor attachment experience, I have found diagnosis helpful to explain behaviour. I guess we already knew beforehand, but having another professional confirm it allays that feeling of “Are we imagining this; are we just handling it badly?” We all have off days. When our son is having a particularly challenging time, I will often mutter the code to my husband: “rather A today”. It conveys that the autistic features are high and serves as a reminder to both of us to bear that in mind when becoming hot under the collar by seemingly unreasonable behaviour. It helps us and others (e.g. teachers) understand why. Diagnosis on its own however serves no purpose unless it enables us to change our approach: “ … we should be focused on the true purpose of diagnosis: to better understand and make sense of individuals and to use that understanding to help us formulate more effective forms of intervention and provision” (Christie et al, 2012, page 17).